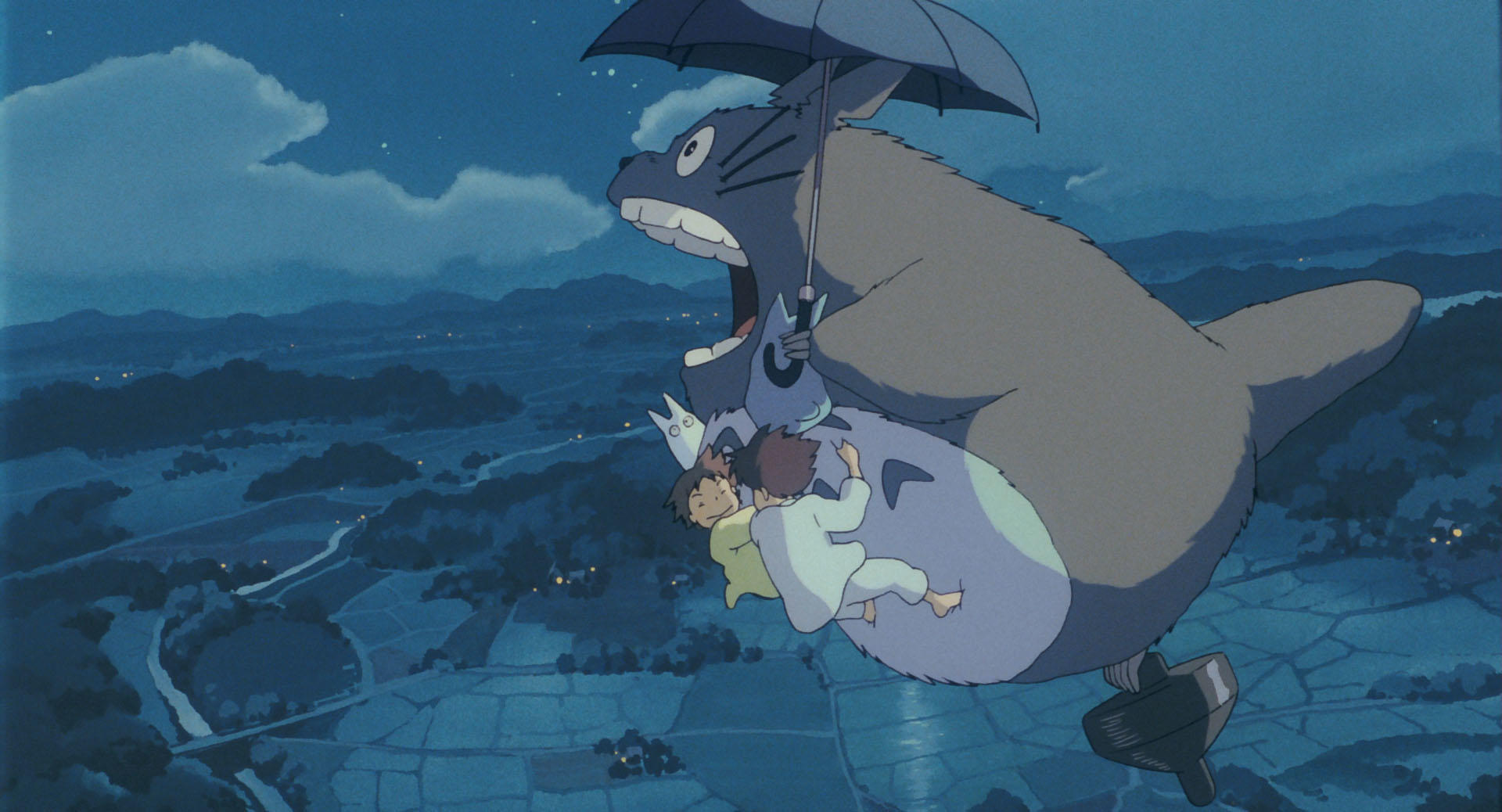

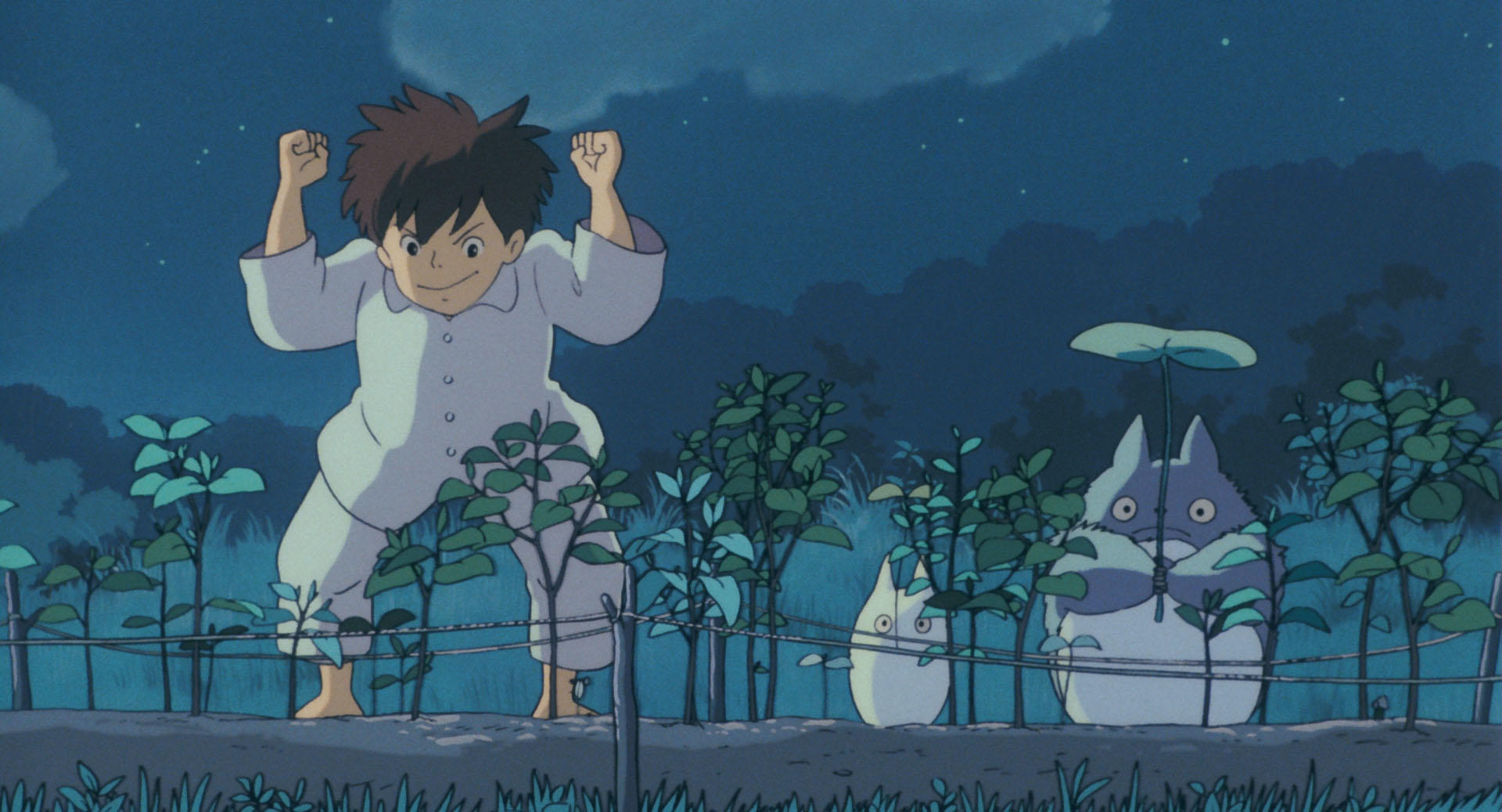

Above: Rewatching My Neighbour Totoro has transformed my commentary on the film; photo courtesy Studio Ghibli.

Unlike those who grew up with Studio Ghibli films, I first experienced My Neighbour Totoro as a young adult. I expected the usual Ghibli formula: an unconfined structure with character growth unfolding the layers of the story. But what pleasantly surprised me was the weight it lent to the childlike imagination.

At first, I scanned for reasons why Totoro would exist, or why this film refused to explain his origins. Unable to answer these myself, I turned to fan theories behind Totoro being a magical fix to the characters’ problems. Was it all just a silly fantasy of a world accustomed to our protagonists’ needs? Or is Totoro symbolic of death? Was the happy ending a sham all along?

I shoved these speculations aside as soon as I realised I had been looking at the film wrong.

I get it – there is no such thing as a ‘wrong’ view of a film. But it was wrong to me; to who I was and what I stood for.

The famous screencap of Satsuki, Mei, and Totoro waiting in the rain; photo courtesy Studio Ghibli.

Here at Leisure and Lapels, I want to champion individuals’ artistic expression, whether it be through fashion or imagination. Totoro has what artistic movements need in its liberation from one path of thought and subversion of expectations. After trying so hard to pick apart this film, I knew I had to let go. The meaning was in front of me all along. The goal was not to abandon critical thinking but to change the way I criticised. By writing this piece, I have learned that critique can be just as insightful and enriching to a conversation when celebratory, neutral, or mere analysis.

Rewatching and studying My Neighbour Totoro helped bring out my inner child.

The narrative follows two young girls, Satsuki, and her younger sister Mei, who navigate their new home in the Japanese countryside. During their explorations, they contact creatures loosely inspired by beings from Shinto folklore (Yōkai), one of these being the title character Totoro, a forest guardian with the appearance of a big, bipedal rodent. Other critters include the mischievous Soot Sprites, and the Catbus, able to zip the girls to any destination they please.

The Catbus with Totoro and Satsuki; photo courtesy Studio Ghibli.

Even the film’s adult characters and authority figures encourage Satsuki and Mei to engage in these folk stories. Their neighbour’s grandmother, whom the girls call Granny, says she saw Soot Sprites as a young girl. Their father, Tatsuo, thanks the Totoro as a ‘forest spirit’ after Mei’s first encounter with him. Despite not getting to see him for himself, he believes in Mei’s sighting, giving value to her perspective on the world around her.

The first half of the film gives agency not to the adults, but to the children. Instead of seeing the adults dismiss what the girls saw, the girls themselves get to insist on what is real. For the children watching who are dissuaded from daydreaming and scolded for wild imaginations, this narrative empowers them as humans with choice. They are able to navigate the story on their own terms, and not through what adults tell them.

Totoro represents a safe place for the girls as they undergo many changes, such as moving house and their mother’s worsening health. Satsuki and Mei cope by developing their own play in the way that kids do, with Tatsuo idly watching over them. The lack of helicopter parenting, sheltering, and explicit danger is extremely refreshing to see in this sort of realism.

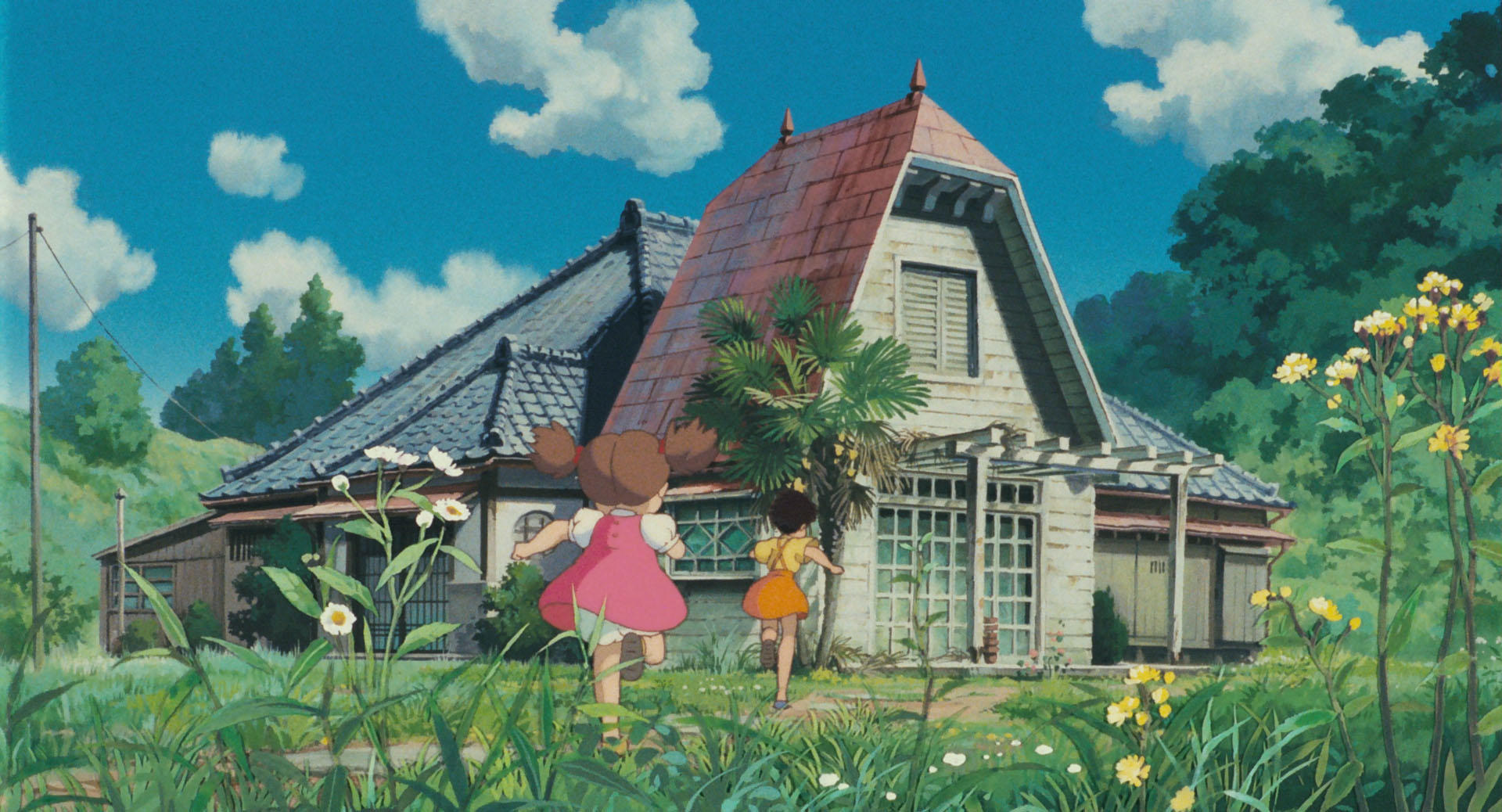

The film’s visuals highlight this emotionally open environment. Scenes and landscapes involve wide, open spaces to imply freedom and movement (although Mei running away near the end of the film could also criticise this). The greenery represents youth and vivacity, which the girls, Mei especially, embody. This autonomy in exploring the natural world leads them, as children with curious instincts, to discover and bond with Totoro.

A wide shot of the girls happily running. Note the atmospheric backdrop; photo courtesy Studio Ghibli.

A wide shot of Satsuki looking for her little sister. The cloudy sky and fields ahead dwarf her in comparison; photo courtesy Studio Ghibli.

Whether Totoro is ‘real’ or not, the beauty of the film is that it does not have to explain why Totoro ‘is’ or ‘isn’t’. But the young girls’ characters and interactions with the spirit world, in contrast, drives the plot forward. Their visualisation of the spirits and their co-operation with them to alter reality (such as making seeds sprout overnight) suggest that the inner child is one of spiritual attunement, and most importantly, growth.

The girls making a tree grow from seeds, with the smaller Totoro spirits; photo courtesy Studio Ghibli.

Meanwhile, the narrative conflict is more abstract than what children are used to watching: this threat of their mother, Yasuko, dying. It is interesting how it is the realism in the story, and not the unknown (Totoro), that induces fear in the characters. The only inevitable thing is death, and the fantasy here aims to distract us until the realism grounds us and the characters alike.

While some Western viewers may be accustomed to the ‘unknown’ as a fear device, benevolent Totoro encourages the girls to form relationships with things beyond human: the spirit world. Yōkai are neutral; they range from good to malevolent. Its direct translation of ‘Spectre’ or ‘Ghost’ however, indicates elements of horror and can easily invoke fear in a story.

Mei’s playful interaction with Totoro helps introduce the creature as something gentle, despite its size; photo courtesy Studio Ghibli.

But is the idea of this bipedal rodent consoling kids in times of trouble really so much different from a magical fairy godmother or a prince charming? In fact, I would go to say that despite it being about, well, a giant happy rat, My Neighbour Totoro offers something closer to home than fairytales do. The inclusion of a sisterly bond rather than a romance between princes and princesses, its endorsement of the child’s point of view, and imagination as a source of healing are all but a few ideas.

As a young adult, I am blessed to have this film in my life. Not only has it reminded me to laugh, sing, and imagine in times of gloom, it has taught me a brighter side to critiquing children’s media in general. There is no such thing as a wrong view of a film, so let mine be bright, celebratory, and dedicated to the inner child we so often overlook in our lives.