by Jason Velázquez

The public has had a fascination with justice, or at least the public meting out of punishment, since at least as early as the Middle Ages. Gathering some rotten produce and taking the kids down to the local stocks, gallows, or executioner’s block is a sure way to turn any Saturday morning into memorable family time.

Podcast (top-left-corner): Play in new window | Download

While plenty of townsfolk likely attended these macabre demonstrations of official state power to see a crime avenged, just as likely is the possibility that some fraction of the drunken, unruly mob neither knew the condemned nor cared what the charges may have been.

PREMIUM CONTENT for Supporting Members, $5/mo. & up.

As the centuries wore on, much of the festive, carnival -esque atmosphere has faded (with notable recent exceptions involving celebrities and sports stars), being replaced by the staid decorum of the modern courtroom. Public participation is still accommodated (sobriety: encouraged, rotten fruit: not so much), however, and the gallery is typically populated by kin of the accused or their alleged victims.

The ability of the aggrieved (or bereaved) to bear witness to a jury’s verdict and the subsequent public pronouncement of sentence is accepted as part of an orderly process that democracies are known for, and that keeps civilians from banding together into vigilante posses, interpreting and enforcing the law in wrathful, chaotic ways. In fact, for the last decade or more, groups of victims’ advocacy groups have taken to the gallery benches to monitor trials with the aim of pressuring the courts to dole out the harshest sentences allowable for the crimes of murder, rape, and others. Some of these groups are run by residents, whereas in some cities, the operations are sanctioned by the local government. In Cleveland, Ohio, for example, the city-run program states, through it’s website, that “Through the presence of a unified community, judges will understand that it is expected that perpetrators be held fully responsible for their actions and punished accordingly.” Other efforts, such as those run by the King County Sexual Assault Resource Center, in Renton, Wash., provide “confidential feedback to 74% of King County Superior Court judges on courtroom decorum, accessibility, and treatment of the parties to sexual assault cases,” and offer their input in developing a set of standards in prosecuting cases of rape.

A change in the wind

In the last few years, a new focus has been directed at the workings of law and order in the United States. In more and more cities and counties, advocates for the accused have begun equipping themselves with the tools and knowledge needed to monitor and assess their local justice systems. Their objective? To bring an end to racial and income disparities in in the courts. Court-watch programs have been activated in New York, Boston, Chicago, and many other jurisdictions that train residents in the collection of data for use in analyzing all the points of contact with a somewhat confusing, often archaic legal framework with demonstrably biased traditions.

Joining the cities that manage the nation’s largest court systems in 2019, Berkshire County will inaugurate its own program of volunteer court watchers. Writer and activist Peggy Kern has been working with Williams College student Mohammed Memfis, the NAACP, Berkshire County Branch, and others to launch the series of training that will put civilian monitors in the seats.

Modeled after CourtWatch MA, focus on education, data

“Our aim is really to, One: make sure that the reforms that we have voted in,” said Kern, the point person for Northern Berkshires for Racial Justice, by phone, “in the form of a progressive district attorney and the criminal justice reform legislation that has been going on in Massachusetts, and, Two: to see how those reforms are being implemented within our courtrooms. Also to educate ourselves about what mass incarceration really looks like, and what the faces and the names of that are — who in our community is being prosecuted, and for what, and how we as citizens can sort of start to change our relationship with the court system and become more active participants in gathering data, and advocating for the sorts of changes we would like to see.”

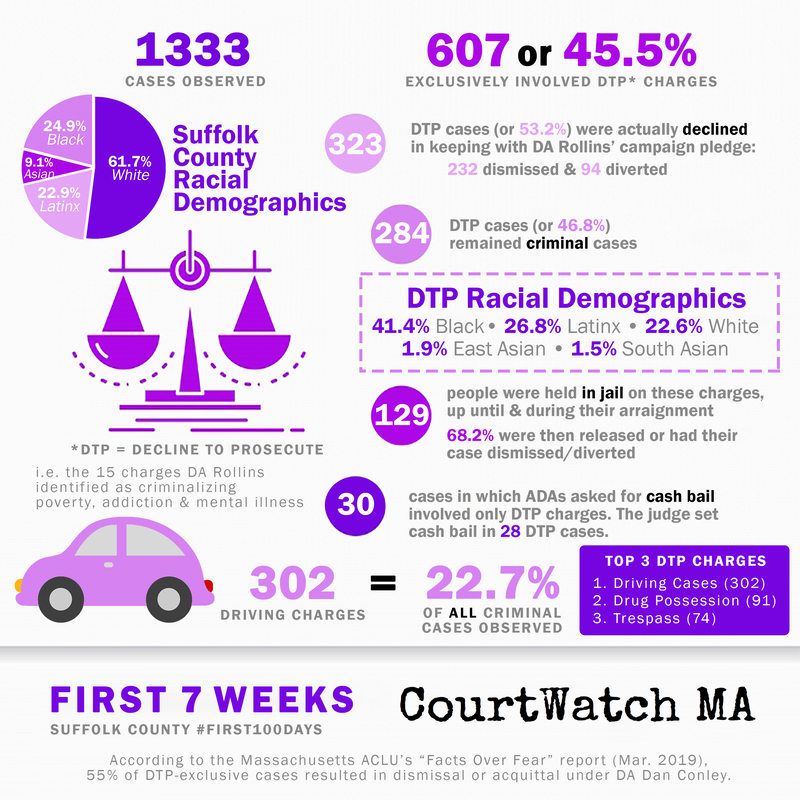

Kern said that the Berkshire County court watch program will closely follow the format of the program in Boston, CourtWatch MA, which has been up and running for several months now. They launched the “First 100 Days Court Watch Project” in Suffolk County to coincide with the election of district attorney, Rachel Rollins, who campaigned as one of new breed of progressive DAs. The group, which has included New England Patriots players Devin McCourty, Jason McCourty, Duron Harmon, and Matthew Slater, made it clear that the voters would hold their new district attorney to her campaign promises of change. For several weeks after being sworn in, Rollins incurred heavy criticism from her supporters and the media, due to her failure to enact some of the reforms she promised during the campaign. Due to a lack of formal policy guidelines from Rollins’ desk, her office’s prosecutors continued to seek convictions on many of the 15 crimes she pledged to place on a “ Do Not Prosecute” list. Pressure from CourtWatch MA and others preceded the rollout of prosecutorial directives from Rollins.

While Americans have generally had a pretty good sense of how their selections on voting day affect the legislation that shapes their towns, states, and nation, less clear is relationship between a lever pulled in November and the levers of legal power that operate all year long.”

Mass incarceration in US demonstrates clear racial bias

“I would say one of the biggest mechanisms,” said Kern, “as far as what has created mass incarceration of American citizens — we now incarcerate more people than any other country on the planet — is the prosecutor, the prosecutor who has chosen to put majority low income, disproportionately people of color, disproportionately people who are in difficult socioeconomic positions into the prison system. So, a progressive prosecutor, which is what we are seeing sort of a rise of across the country in many areas, including Berkshire County, is a prosecutor who understands what mass incarceration is, and views their role, as I guess, the easiest way to put it is to stop prosecuting a lot of cases.”

City University of New York law professor Steven Zeidman, in a recent op-ed in the Gotham Gazette echoed Kern’s observations. He noted that he found it very telling that, in a recent article in Mother Jones profiling Tiffany Cabán, the district attorney candidate for Queens, the author wrote that Cabán “has a radical vision for the position: she says she’d incarcerate as few offenders as possible.”

Zeidman wrote “…decades of hyper-aggressive policing and punishment have made such a fundamentally humane and moral statement seem not just progressive but “radical…” He offers up a modest list of 13 points to which any district attorney candidate claiming to be truly progressive should pledge. Some of the recommendations are flavored with New York–specific concepts, but most would likely strike voters as common sensical:

• no plea offer unless the accused waives their statutory right to a prompt grand jury presentation.

• commit to not conducting any interrogations unless and until the accused has been provided with an attorney?

• insulating prosecutors from their duty to provide the defense with exculpatory evidence.

The rest can be found by reading the full piece at the Gotham Gazette, a sister CIVIL publication to the Greylock Glass.

Incarceration damages, dehumanizes

A main objective of court watch programs is to minimize harm to the community from crime in ways that minimize harm to the community through unnecessarily strict (or just plain unnecessary) sentencing. CourtWatch MA declares, “Every single hour a person spends in detention is harmful and every time cash bail is imposed it can have disastrous consequences without any positive impact on our community.”

Mohammed Memfis, a sophomore at Williams College who is working with Peggy Kern and the NAACP, Berkshires Branch to initiate training sessions for volunteer court observers, has worked in the offices of two district attorneys, including in Berkshire County. He notes that in addition to data collection, the program hopes to humanize the defendants, within the context of their communities.

“We sort of also want to use that that qualitative side to tell the stories of defendants,” said Memfis, by phone. “It’s one thing to see it on the news or to interact with a piece of media to say there’s a person that did this— sure, this is the the punishment they deserve. But without that story, you don’t get at the root causes, and especially in Berkshire County, where there are, housing insecurities, drug addictions, and a lot of deep poverty that exists, those are things that are completely ignored. And right now we’re using prison as a way of solving those problems. And it really shouldn’t be that way. And so those are the two main bridges that we’re trying to connect.”

Berkshire County may have elected, in 2018, a district attorney open to these more complex issues impacting public safety and justice. Andrea Harrington, who unseated incumbent Paul Caccaviello in a bruising primary, and then general election (you can relive that bloodbath if you must), came under immediate fire from some quarters of the county for her reformist tendencies.

By phone, Harrington said, “Oh, yeah, I mean, for me, I grew up here in Berkshire County. My family’s been from Berkshire County for a long time. But spending time in District Court, seeing how our community was struggling with mental health challenges, substance use disorder, and you really, really can see how the effects of the system on poor people. It’s very, you just see the challenges show dramatically in the courts. It’s very eye-opening.”

Wave of progressive DAs creates space for change

Harrington and Kern have been in communication about the formation of the court watch program. Most successful implementations of these initiatives have enjoyed at least a civil relationship with a district attorney who campaigned on progressive platforms.

“So yes,” said Kern,” we have what I would describe as a progressive-leaning prosecutor now and in Berkshire County, which is wonderful news. Andrea Harrington has already addressed issues like the cash bail system, and how cash bail has targeted and resulted in the pre-trial detention of low income people who can’t afford the bail amounts that are assigned to them by courts. This is Massachusetts law now that you cannot hold people on bail amounts they can’t afford, for example. [District Attorney] Harrington has been clear in public statements that she will not be seeking cash bail in the vast majority of cases. So things like that certainly indicate to us that she is progressive. She certainly talked a lot about the issues of mass incarceration and, you know, racism within our system during her campaign. So we’re really excited about her being our new DA, and we sort of can’t wait to see these changes put into action in our courtrooms.”

Disparities of justice outcomes between caucasians and people of color, says Harrington, is high on her list of priorities.

Inequitable justice system fails individuals, communities

“My view of racial equity in Berkshire County in the courts,” said Harrington “is that that is a subject that has long been ignored. And I think that the really, really exciting thing about my campaign was that, for the first time, we really had a community-wide conversation about equity in the courts. We don’t have a lot of data about how people are are treated in the court system based on things like race or ethnicity. But we do know that African Americans were charged five times higher median bail than white people in Berkshire County—that’s a massive disparity. It is a much larger disparity than what is seen in more urban parts of Massachusetts. Another data point that we have is, when you look at rates of incarceration in Massachusetts, we have some of the lowest incarceration rates in the nation. But if you look at the rates of incarceration for African Americans, we have the same kind of levels of incarceration as they do in other states. So we’re much better, you know, at not jailing white people than we are at not jailing black people. And this, a lot of this stuff, starts in the district attorney’s office. And I’m very committed to determining policies that ensure that we treat people equitably but also to keeping data and tracking what we’re doing. So that we’re not just going on anecdotes—we’re going on actual facts, so that we can rectify these disparities that we see.”

If cooperation does truly occur between the watched and the watchers, facts and data will undoubtedly pile up very quickly, as it has for CourtWatch MA and other programs. Mohammed Memfis, the student assisting in the effort envisions a wealth of information being generated on both sides of the gallery bar.

Training eyes and ears for long-term data collection

Memfis described a varied approach, “Two ways: we’re going to compile this data, and we’re going to ensure this data is public and available to anyone who can access it on a computer. But we don’t just want to throw up a bunch of numbers and sort of that be the end of it. The goal here is to actually make, for instance, reports, to make those infographics, to make those statistical breakdowns of what’s being analyzed, and watched in the courtroom. And that’s something that’s also going to be made public. Peggy may have spoken about this, but the Berkshire County DA’s office has also stated that they are also planning to do something to release this data about their cases. And so when that does come along, we do want to work in tandem, so that we can review these results.”

Memfis explained that the court watch program will have the power to make real, and immediate, something that many Berkshire residents may perceive as a distant discomfort for nameless, faceless individuals.

“At the very bare minimum,” said Memfis, “what we’re striving for is to have an informed voter, right, someone who isn’t ignorant of what is actually going on in their local community, but rather someone who has an idea of what’s happening in their criminal justice system, just as they are informed about what’s happening in some other political sphere of their lives. And that is what helps create an informed participant, having that awareness and being knowledgeable, because the truth of matter is, a lot of folks also don’t know this issue exists. And a lot of folks who do know this issue exists, may think that it’s not necessarily an issue for Berkshire County— that’s not the case. It’s an issue everywhere. And so what we’re trying to get into that dark box and bring that out, we’re trying to shine a light on it and give folks the opportunity to easily access these materials and to be influenced and impacted by it.”

Harrington says she’s aware of many of the benefits of programs like the one forming in her own county. The activities are likely to inform the public both about the justice system in general and the decisions made and policies pursued by those within that system here at home.

DA looks forward to education, also accountability

“I really see the court watch program primarily as an education program, and also as a transparency and accountability tool. So, just touching on the education piece first, in my race for district attorney, there were record numbers of people that voted both in the primary and in the general election for this race. And part of that is because people were interested in the race, and people were interested in the race because people started to become aware of the fact that district attorneys are elected and started become aware of what they actually do. And I found that when your people being educated, it makes them more engaged. And it helps for people to understand like the issues and what’s going on. And for people who have never been involved in the system before, it’s hard to understand how things work. So I think educating people about what’s going on in the courts is really going to help us, as a community, to have meaningful, sophisticated conversations about criminal justice policy that really affects us all, every day, because it affects public safety and affects the people who end up in the system. And it affects our employers, and their workforce development. It affects our schools. So I see the court watch program has been hugely valuable.”

Harrington is hardly ignorant of the fact that more information making its way to the public, is, well, creating a more informed public.

And then, hitting on the transparency and accountability piece. You know, if you’re not sitting in court, you don’t necessarily know what happens. I mean, people certainly can read the newspaper. I mean, my office certainly is really trying to communicate more broadly with the public about what we’re doing. But I think that the court watch program is great way to hold people accountable for what’s happening in the courts. You know, of course, it’s a great way to hold me accountable for what’s happening in the courts. And I welcome that. And I welcome that feedback. Because I think it’s going to help everybody to have better conversations—smart, informed conversations.

Memfis also acknowledged the reality that some people have had very little experience in courtrooms, but said that getting over that awkwardness just takes time.

“Once again,” he said, “folks are unfamiliar and may be uncomfortable walking into courtroom—that should not be the case, we hope, by the end of these trainings. That is removed, and folks are able to walk into District Court in North Adams or in Pittsfield or in Great Barrington. And to really begin to walk in, sit down, and assess what’s going on. So basically, there’s this sheet that they’re going to be provided with, and they’re all going to have yellow folders so that the court knows that there are court watchers there. And the purpose of that is going to be sit there can record that data. And basically, over time, that will be compiled so that we can get a pretty expansive overview of the cases that we’re seeing in Berkshire County and how they’re being treated by prosecutors.”

Many of the pieces of information that volunteers will be gathering will be apparent visually, or available by observing and recording raw facts, according to Memfis.

“What are some of the very basic superficial thing like, what are the charges, right? What are people actually being charged with? What are the recommendations that the prosecutors are asking for? Is there an officer involved in this? So what is it the officer advocating for? What is the decision of the judge, ultimately, in the case. But also, some of the other information that may be helpful in terms of compiling it — things that you can just sort of get from there on the spot may be some of the basic historical facts about the individual, the the sex of the individual, all things that are very easy to attain some in the court.”

Kern encouraged anyone interested in finding out more about the program to attend one of the upcoming training opportunities.

“So we will be launching a bunch of trainings in the Northern Berkshire area,” she said. “Our first will be May 9, which is, I believe, next Thursday, May 9, at the Tyler Street lab in Pittsfield at 6:00 p.m. You can find more information by contacting the NAACP Berkshire County chapter. They are helping us organize and they are a good point of information on this program, and you can also check their Facebook. We will be creating a Facebook invite for the events, which will be on the NAACP, Berkshire

Branch Facebook page.”

Activism from many sectors building for decades

A common theme throughout this endeavor has been to use the collected data to find ways to continue using law enforcement where it makes sense, but to divert defendants to other destinations within the broader system that may have more positive outcomes, both for the accused and the community. Kern notes that behind many prosecutions may lie circumstances that, if addressed within appropriate treatment or assistance contexts, may more successfully short-circuit a cycle of incarceration.

“And also the telling of stories,” said Kern, “We really want to put faces and names to our court system. You know, it’s one thing to hear the statistics about low income people being criminalized; it’s another thing to actually witness, you know, a 19 year old young man be arraigned on charges, knowing that perhaps his background has been full of trauma, and full of challenges that are more related to finances than to this person being a bad person or whatever. There’s context and nuance to everyone. And that’s part of what we sort of want to illuminate.”

District Attorney Harrington sees a convergence in issues that have led to a moment in American history when a broad swath of the electorate is ready for humanizing reform.

“This activism has been going on for decades,” she said. “But now it’s starting to really resonate with people, I think, because so many middle class people have been affected by the opioid epidemic. And the fact that now more different kinds of people from throughout our community are interacting with the criminal justice system and are seeing the way it has been devastating for communities of color in terms of rates of incarceration. It also really doesn’t work well for poor people. It doesn’t work well for people with mental health problems. So, so many people that end up in the criminal justice system have mental health illness. It doesn’t work well for people who are struggling with substances. So this activism around criminal justice, like this has been a long time coming, and it’s been the result of the work of a lot of great leaders.

She suggested also, that a possible side effect of current events on a national scale may spur on civic participation.

“And, too,” she noted, “I do think that with the kind of…Trump-effect, that definitely people are more civically engaged, because I think they recognize that a system of laws, and the rule of law—it doesn’t just happen. We have to work for it. We have to fight for it by paying attention, by voting, by raising our voices.”

![Berkshire County Courthouse, photo by Alexius Horatius; [CC BY-SA 3.0] via Wikimedia Commons.](https://www.greylockglass.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Berkshire_County_Courthouse_2_sm.jpg)