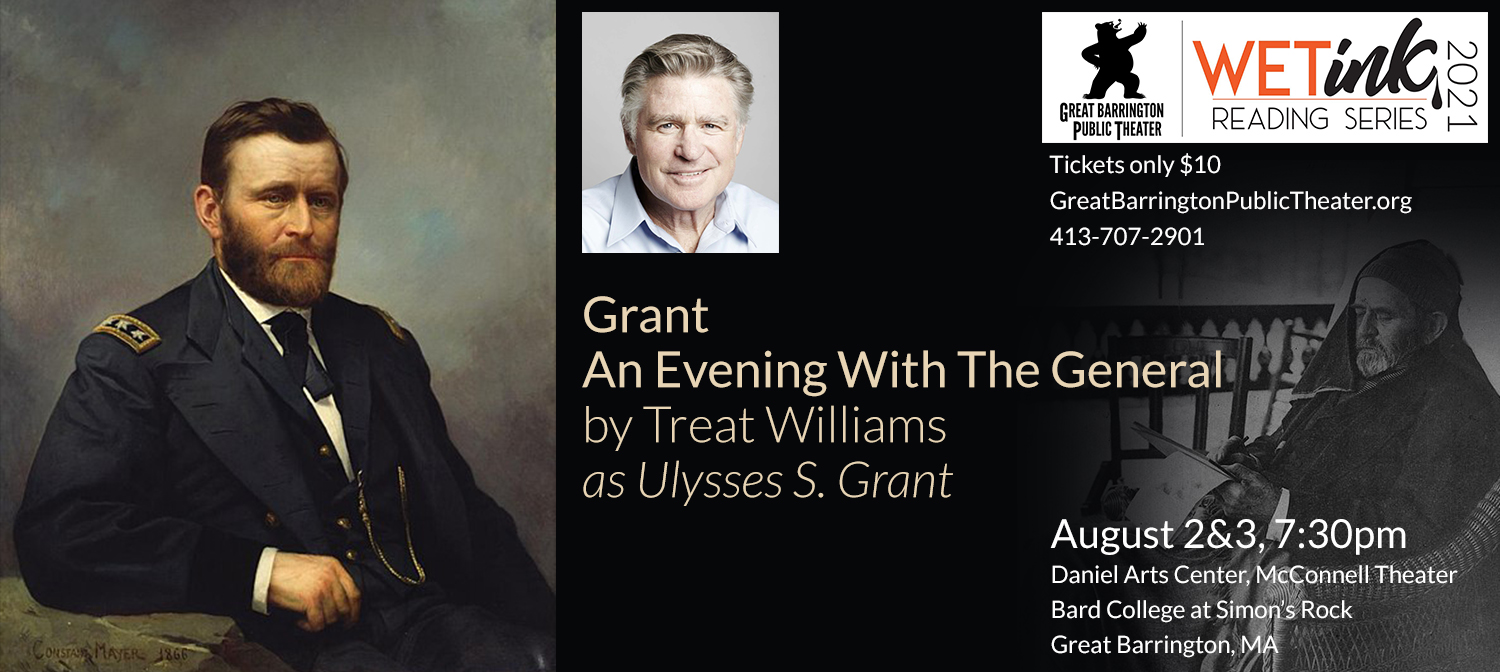

Grant: An Evening With the General is part of the Wet Ink series at Great Barrington Public Theater. Treat Williams gives a second reading on August 3, followed by Leigh Strimbeck’s Queen of the Fenway Court on August 4. www.greatbarringtonpublictheater.org/productions

There are a few things I need to share before I get to the event itself. Once upon a time, or half a lifetime ago given his current age of eighteen, my son appeared in a movie with Treat Williams. “Halftime,” directed by Joe Cacaci, featured Mr. Williams & a rag-tag band of (amateur) pre-teens. The short was filmed in a locker room not far from where I write these words and received warmly at BIFF 2013 (Berkshire International Film Festival). Besides the monologue composed by Richard Dresser, I don’t know that Mr. Williams addressed any words toward my son, who played something like “sturdy / disgruntled youth” and enjoyed the premiere at the Mahaiwe far more than the actual work that went into it.

Like my relationship to Treat Williams, my personal history with the Daniel Arts Center at Simon’s Rock is likewise complicated. I have sat through any number of Berkshire Pulse recitals and Berkshire Fringe productions over the years, not to mention the Queer Asian Film Festival that Simon’s Rock students hosted in the early aughts. Most recently, my wife and I enjoyed the big-screen (and I mean BIG SCREEN) exploits of Mick & Keith and company last summer. Mahaiwe Peforming Arts Center’s 2020 drive-in series offered Martin Scorsese’s Shine A Light (2008), which captured the Stones in a recent (shall we say “mature”?) concert at New York’s Beacon Theater.

Setting aside my own predilections and preconceptions — as if it were possible to do so — I was not sure what to expect from Mr. Williams’s reading. I knew of Ulysses S. Grant as a popular military leader and controversial president, a reputed alcoholic and the face of the $50. And I knew of Treat Williams as an actor of many decades and many media, from Broadway blockbusters (Grease) to police procedurals (Law & Order: SVU), from big-budget epics (Once Upon a Time in America) to no-budget passion projects (“Halftime”).

After a quick introduction from director Jim Frangione, who also read stage directions along the way, Mr. Williams took to the stage. It was bare besides a dark-wood lectern (for the script — his own, as he is both the writer and the reader) and a metallic bar-stool (for bottled water and an iconic stogie). Clad in a dark suit and an oxford shirt, Williams showed fine voice from start to finish. He remained behind the lectern throughout; the stage directions promised costume changes and movement about the stage, which will nicely augment Williams work to capture and share Grant’s persona. Williams and Frangione might also consider a musical score and more extensive use of photographs as the project moves toward a full theatrical production.

Two moments stood out in the reading. The first occurred when Grant spoke about his relationship with his wife. Williams actually broke up when extolling Julia Grant’s virtues and needed a moment to gather himself; he professed afterward that this storm of emotion took him by surprise. The visceral impact on performer and audience alike suggests that the writer might give that relationship more importance in the show.

The other transcendental moment came as Grant covered the Battle of Shiloh (which he ruefully reminds us is a Hebrew term relating to peace). In this instance, however, rather than simply recounting the events at some remove, the former commander relives the chaos of battle and showers commands from the stage as if his audience might hold the line or push ahead on the left or bring up the cannon. That scene resonated and is sure to kill with all the trappings of a full stage production. Perhaps Williams and Frangione should consider reworking the script so as to build around those sorts of set pieces, rather than relying on long stretches of expository or reflective prose that hold less inherent dramatic value.

In an interesting choice, Williams ends the show with Grant and Lee agreeing to peace at Appomattox. Asked about this decision at the talkback, the playwright explained that there was simply “too much to cover” to include Grant’s two terms as president. (The fact that Grant ended his own memoirs in 1865 is also probably relevant.) Perhaps less information about Grant’s childhood alienation, military success in Mexico, drunken decommissioning in California, or dismal business ventures would free up time for the White House years. (And Mrs. Grant might feature in those segments in a way that she could not be present in his tales of battle.)

Last but not least, there is the matter of framing. The general begins by welcoming us into his new residency in upstate New York, knowing full well that he will not leave this place before cancer claims his life. With support from Mark Twain, the nearly-destitute Grant received a publishing contract guaranteeing massive royalties, provided he completed the book before his demise. Grant knew he was up against the clock and pushed hard to vanquish that enemy as he had so many others. He finished the work mere days before his death, and the well-received volume netted his widow Julia nearly half a million dollars in succeeding years. By using that narrative frame more fully throughout the play, and closing the show with the culmination of that life in prose, Williams will offer his audience a more complete emotional experience.

Lest we struggle to find contemporary relevance of Treat Williams’s study of this complicated historical figure, the author / reader reminded his audience in the talkback that “We are all Americans,” then as now. Moments of historical crisis, whether the Civil War of the 1860s or the uncivil unrest of recent years, tend to bring out the worst in society. What better time to celebrate the legacy of a man who did his level best to dig into the most heated controversies of his day in a way that demonstrated “moral courage” in the service of “an honorable cause” (two of Grant’s favorite phrases)?

Williams cited two main objectives underlying the project. Like Grant and his memoirs, he was looking to make some money in the face of financial hardship. (Needless to say, the past 18 months have been brutal for those in the performing arts.) In addition, and perhaps more importantly, he wants to “give Grant his due.” One cannot know the eventual outcome of Williams’s efforts beyond a second reading tonight. (Go if you can!) But this is what I am left with, in the meantime: the image of an aging man, alone on stage. He speaks to a nominal audience, attempting to cajole or to convince them in the moment. But he has his mind set on a larger score: the immutable verdict of immortality. Who among us can he be sure that even a single fact or date or word will live on once he has left this realm?